Digital Technology and Printed Maps as Tools"

Devorah Sperber, US Representative

26th Ljubljana Print Biennale

June 23 - October 2, 2005

Catalogue Essay by Marilyn Kushner

Brooklyn Museum

New York/

USA

Curator: Marilyn Kushner

The Brooklyn Museum, housed in a 560,000-square-foot, beaux-arts building, is the second largest art museum in New York City and one of the largest in the country. its world-renowned permanent collections include more than one milion objects, from ancienct Egyptian masterpieces to contemporary art, and represent a wide range of cultures. Only a thrity-minute subway ride from midtown Manhattan, with its own newly renovated subway station, the Museum is part of a complex of nineteenth-century parks and gardens that also includes Prospect Park, the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, and the Prospect Park Zoo.

How

We See

Digital Technology and Printed Maps as Tools

In 1934 Paul Valéry wrote,

Our fine arts were developed, their types and uses were established in times very different from the present. .. In all the arts there is a physical component which can no longer be considered or treated as it used to be, which cannot remain unaffected by our modern knowledge and power. For the last twenty years neither matter nor space nor time has been what it was from time immemorial. We must expect great innovations to transform the entire technique of the arts, thereby affecting artistic invention itself and perhaps even bringing about an amazing change in our very notion of art.

Today, almost 75 years later, we find ourselves in the same circumstances. Our "very notion of art" is in great flux. In terms of the medium of printmaking, we are, indeed, in a watershed period. At the beginning of the twenty-first century computer technology is creating a revolution in mark making and by extension, other media as well. And, digital technology seems to have revolutionized not only the field of printmaking but also the way in which some artists are looking at the world. Yet, we might ask ourselves if it really is so different.

Valéry wrote that the fine arts were "established in times very different from the present." Indeed! Our times are very different from the beginnings of printmaking. In the fifteenth century printmaking was established with the art of the relief print and engraving. Now with the advent of computer technology, an invention as innovative as was Gutenberg's moveable type in the fifteenth century, we are witnessing another momentous development. The computer has given us a new way to produce prints. But it has also affected the way that we see not only printmaking and by extension photography, but art in general. And yet, one might make the case that this is not entirely new - it is just occurring with a new tool. Remarkably, artists in the nineteenth-century were seeing in this manner without the assistance of a computer. Let us cite a few examples.

Claude Monet once explained to artist, Lilla Cabot Perry, "When you go out to paint, try to forget what objects you have before you, a tree, a house, a field or whatever. Merely think here is a little square of blue, here an oblong of pink, here a streak of yellow, and paint it just as it looks to you, the exact color and shape, until it gives you your own naive impression of the scene before you." When Monet created his images he did just that, as close examination of his works reveals the patches of color about which he speaks. Now the computer does that for us. One must recognize that then too, Monet was employing new technology for he was availing himself of brilliant pigments that were new on the market, pigments that could be squeezed fresh out of the tube. And, he was combining his colors in a manner that resulted in the pulsating and refreshing scenes for which he is renowned. Today, more than a century later art works are being created that can be compared with what those groundbreaking impressionists were doing then.

The first impressionist exhibition opened on April 15, 1874. Two weeks later Jules Antoine Castagnary would write, "The common concept which united them as a group and gives them a collective strength in the midst of our disaggregate epoch is the determination not to search for a smooth execution, but to be satisfied with a certain general aspect. ...They are impressionists in the sense that they render not a landscape but the sensation produced by a landscape." Today, once again some artists are rendering sensations, impressions, rather than reality. We can find ourselves looking at re-creations of images that we have seen before; images that are themselves creations of imagined realities. And our twenty-first century renditions are sometimes based upon printed renditions of the original images.

Art historian Meyer Schapiro wrote about Georges Seurat that his "dots may be seen as a kind of collage. They create a hollow space within the frame, often a vast depth; but they compel us also to see the picture as a finely structured surface made up of an infinite number of superposed units attached to the canvas." Seurat's A Sunday on La Grande Jatte was created in an era of mechanized industrialization, emerging mass-production and extensive conversation about scientific theory, and especially color theory. As such, in addition to being read as collaged units on a canvas the small dots also must be seen as uniform mass-produced units of a structural whole relating to a burgeoning mechanized society of the late-nineteenth century.

Devorah

Sperber

After Dali, After Harmon (installation view), 2003-2004, chenille

stems, mixed-media frame

When Devorah Sperber deliberately pixilated her image in After Dali, 2003-04, she too was reacting to the contemporary mechanization or, in this case digitization, of her society and, indeed the world, in the early twenty-first century. And, when she made After Vermeer I, 2003-04, she made her own pixilated image using objects often associated with the late nineteenth century-spools of thread. Like Seurat, more than a century before her, Sperber created her imagery on the basis of this new way of seeing, for example the pixel. In After Vermeer I, the pixels are represented by old-fashioned spools of thread.

One might also maintain that artists like Monet and Seurat had actually pixilated or at least scientifically analyzed their manner of viewing objects in the nineteenth century, and they developed their new way of seeing without the tools of a computer. When considered in this context, their achievements become even more astonishing indeed! What we use a computer to do today, the nineteenth-century artists did naturally.

While some may posit that this issue strays from the graphic mode, it can serve as a good example of the manner in which digital technology that first affected the printed artwork has now spilled out into other media. Sperber's work is based upon the printed image without which she could not realize the three-dimensional object. Her computer print maps out the way she will produce her art - how to construct the three-dimensional color image and, in a sense, it has given her, and the viewer, a way of seeing that might be based in nineteenth-century theories but facilitated by twenty-first technologies.

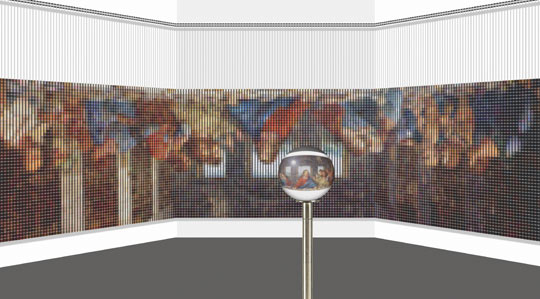

Devorah

Sperber

After The Last Supper (digital rendering), 2005, spools of thread,

aluminum ball chain, stainless steel hanging apparatus, acrylic viewing

sphere, metal stand, 17.8 x 884 cm

Devorah Sperber's re-creations of Leonardo da Vinci's The Last Supper and his Mona Lisa are full-scale three-dimensional renderings of the images that began with computer prints which she considers "maps." These maps pixilate the masterpieces and helps Sperber determine how she will construct her works using spools of thread that will replace the pixels on the two-dimensional maps. She used more than 21,000 spools of thread to produce The Last Supper. When viewed with the aid of optical devices, the spools of thread are synthesized into an image that is famous the world over. These goals are very similar to those of both Monet and Seurat working one hundred years ago. Playing off of the ability of the brain to integrate small parts into a whole, all of these artists de-construct their images so that the brain can re-construct them using small bits of information that the artists give to us. The nineteenth-century artists relied upon popular scientific theories; Sperber and other early twenty-first artists rely upon computer prints that pixilate the images for us.

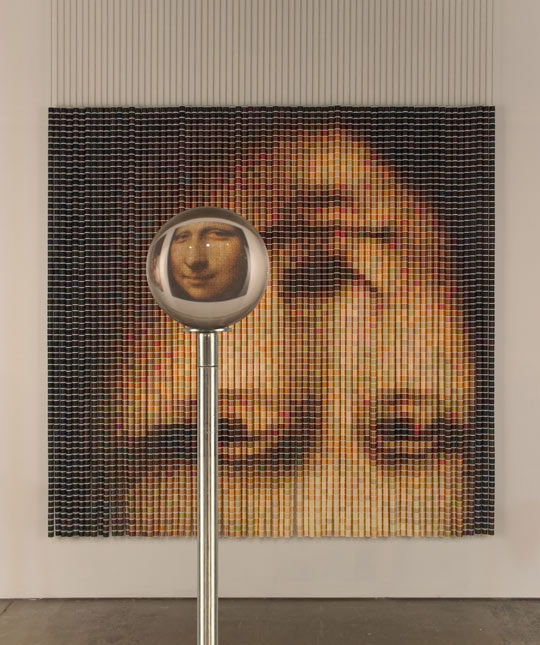

Devorah

Sperber

After The Mona Lisa 2 (studio view), 2005, spools of thread, aluminum

ball chain, stainless steel hanging apparatus, acrylic viewing sphere,

metal stand, 216 x 218 cm

Sperber addresses issues of the way we think we see vs. the way that the brain processes. Her thread spool pieces are actually installed so that the image is upside down. She described the work:

When seen with the naked eye, the spools of thread will appear as an abstract arrangement of colored blocks/3D pixels, further abstracted by the fact that The Last Supper imagery will be upside down and backwards. … Clear acrylic spheres [placed in front of the installation] will rotate the imagery 180 degrees back to the correct orientation and condense the individual pixels/spools of thread into recognizable images. In addition, the spheres will offer monocular views of the work, accenting the illusion of three-dimension as it exists in flat paintings. Leonardo da Vinci understood that the illusion of three-dimensions in paintings was derived from monocular, not binocular vision.

By using the computer printout of the masterpieces as the basis of her work, Sperber has taken the traditional print one step further, and produced a three-dimensional image that, similar to a traditional print, could easily be editioned.

Devorah

Sperber

After Vermeer (detail view), 2003-2004, spools of thread, vinyl

tubing, aluminum hanging apparatus, acrylic viewing sphere, metal stand,

230 x 244 cm

Marilyn Kushner is the curator of prints, drawings, and photographs at Brooklyn Museum of Art, Brooklyn, NY.

Artist's Statement

I am interested in the link between art and technology, especially the manner in which the eyes prioritize what they see and the definition of reality as a subjective experience vs. reality as absolute truth. The act of seeing, how the human brain makes sense of the visual world, is a concept that is basic and yet enormously intriguing to me as a visual artist.

My work looks at merging art and science as experiential components vs. intellectual concepts, utilizing the element of surprise, which activates the temporal lobe. This is best described as the "WOW" experience, which occurs when the external world does not correspond to the brain's inner expectations.

While many contemporary artists use digital technology to create high-tech works, I strive to reduce the presence of technology by utilizing mundane materials combined with a low-tech, labor-intensive assembly processes. I place equal emphasis on the entire recognizable image as on the manner in which the individual parts function as abstract elements. In that process I select materials based on aesthetic and functional characteristics as well as for their capacity for a compelling and often contrasting relationship with the subject matter.

By using three-dimensional thread spools to reproduce Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa and The Last Supper I will reintroduce aspects of the original works of art, which are often absent in reproductions. These include the effects of monocular vision, scale, resolution, and spatial frequencies on vision. My intent is to reintroduce these dynamic aspects in the mind's eye of the viewer.

When works of art are mass reproduced through prints, posters, postcards, books, and the Internet, the reproductions can easily replace the original artworks in the mind's eye. These imagined images lack important aspects of the original works; factors such as context, scale (even when accompanied by dimensions), the intended relationship of the viewer to the work, and the work to site. The Mona Lisa and The Last Supper are prime examples of the disparity that can exist between original works of art and the images seen in the mind's eye. The numbers of people who haven seen these paintings in person are relatively few when compared to the vast numbers of people who have seen reproductions or "reproductions of reproductions." I suspect that most people are surprised when they see the original works in person and experience the relatively small scale of the Mona Lisa (30 x 20 7/8"), the subtle effects of Mona Lisa's elusive smile, the relatively large scale of The Last Supper (15 x 29'), the three-dimensional illusion of the mural as an extension of its rectory site, and its current restored condition.