Whitehot

NEW YORK

May 2007, WM issue #3: Devorah Sperber Brooklyn Museum

The Eye of the Artist: The Work of Devorah Sperber

Brooklyn Museum, January 26, 2007-June 17, 2007

Perhaps one of the greatest accomplishments an artist can claim in the postmodern age isn’t just to get people to care, but to get people to come. With the plethora of media outlets, representations, and recycling of representations (that become even better known than the original), the fact that museums—especially art museums—can continue to get people in the door should be nothing less than shocking to our oversaturated sensibilities.

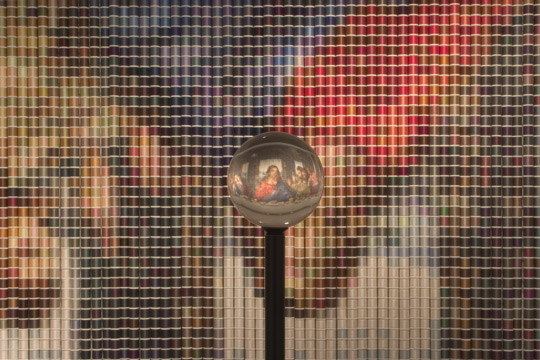

And this is one reason why Devorah Sperber’s exhibit entitled, “The Eye of the Artist: The Work of Devorah Sperber,” at the Brooklyn Museum, succeeds so profoundly. Having seen an image of the exhibit (included here), in which a spherical lens reconciles a vast set of otherwise incomprehensible colors into Leonardo Da Vinci’s The Last Supper, I didn’t just think, “That sounds interesting, I’ll have to look into that,” I thought, “I have to see that.”

The exhibit consists of five installations of varying size, in which hundreds to thousands of spools of thread are strung together and hung upside down so that the image they recreate becomes an enormous, unwieldy version of a painting that we would otherwise recognize as Van Eyck’s Man in a Red Turban; Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, and The Last Supper; and Picasso’s Gertrude Stein. In two smaller installations, Gertrude Stein and the Man in a Red Turban are cut in half and placed against their mirror image, creating two new representations that show off the odd proportional features of the subjects.

Noticing those odd proportions, and attempting to take in the massive spool installations are all part of Sperber’s intention to deconstruct the act of vision—to understand the way we view art, and how we reconcile images—both biologically and artistically. Sperber recently discussed her work along with Bevil Conway, a neurobiologist at Harvard Medical School, and Jennifer Noonan, an art historian who works on the history of color, at a panel discussion at the Brooklyn Museum. These explorations, Sperber noted, began with “observing people looking at my work.” Of the five installations, four are portraits, and it is fascinating to note that 90% of portraits have one eye in the direct vertical center of the canvas. Each of these installations work from that central eye, and the way we observe the painting in relation to it.

Perhaps because of this primary interest in the way that people view her work, Sperber’s installations also help us understand exactly how we look at the iconic paintings she herself deconstructs. In Sperber’s After The Last Supper, the bright red and blue, triangular Jesus in the center is immediately recognizable (if a little distorted). In fact, one recognizes this painting almost solely from this relatively insignificant swath of color in the center. However, the most interesting part of the installation isn’t Jesus, but the overwhelming trail of incomprehensible blacks, browns and navies that surround him. When seen in the vast spool recreation they are impossible to make sense of, but when viewed through the optical lens, the murky apostles pop out of the darkness—taking on their bodily shapes and appropriate ominousness. In a way, this piece and all of the others in Sperber’s collection recapture the drama that was once inherent to these paintings. A drama that has otherwise become so commonplace that we barely still perceive it. Without falling into trite representationalism, Sperber forces us to reconsider images that we have grown comfortably accustomed to seeing, and to experience them again with new eyes.

The installation after Van Eyck’s Man in a Red Turban is just as dramatic. Under the lens, the turban seems to balloon outward, and, like a funhouse painting, not only do the man’s eyes follow you, but so does his head as you turn around the spherical lens. The spools take on a depth that we take for granted in our own sight, and I couldn’t help but wonder that this is what it must have felt like for the first viewers of Caravaggio (or even for that matter, the first time one comes upon a Caravaggio) to become immersed in the recesses and shadows of his subjects.

The enlarged portrait that hangs towards the back of the exhibit, which is many times the size of the original Mona Lisa, takes up the same amount of space that the painting seems to take up in our cultural consciousness. (A smaller version that represents the actual size of the portrait is also on display; to the point that the Mona Lisa is one of the singularly most recycled images of all time, Sperber remarks ironically, “In some ways the life-size Mona Lisa on display here is more accurate than all of the posters, Internet images, and other things that we’ve seen.”) Roughly the size of the Man in the Red Turban, which hangs opposite, this version of the Mona Lisa focuses on her enigmatic smile. Unlike in the Van Eyck portrait, however, the optical lens for this installation was corrected for the bulge that made the red turban balloon like a fun house mirror. Oddly, it gives Mona Lisa a kind of distorted and wider smile than we normally think of her having in the original. And yet, it stays true to life, seeming only to reflect the obsessive cultural attachment we have to the smile of a woman in what is otherwise a somewhat goofy, nondescript painting.

After recently seeing the Mona Lisa for the first time in Paris, I was shocked at how little I felt in seeing it in real life. It was as if all of the representations that I had seen of it over the years had emotionally sucked the painting dry. That anything can breathe life into this image (life that even the image itself can’t muster these days), and make one re-examine something that we now take so for granted is a feat of the greatest proportions. Sperber has made a collection of pieces that one just wants to see, in part because of the great disbelief that comes from seeing a mere image of what she has created. This is a disbelief that she knowingly plays with in her pieces: How does this mass of strange colors become what I know as The Last Supper? And how ironic it is that it is the distrust of the image that compels one to experience Sperber’s work up close—to understand what it is about our vision that makes vision itself so rich and so mysterious. And how we wonder what power those original paintings must have had when they were at the height of their own monopoly over the drama and grandeur of sight. -- Marika Josephson

Marika Josephson writes about art and politics, and is a graduate student in philosophy at the New School for Social Research. about whitehot